The Next Big Short: Hidden Risks Behind Private Equity's $8 Trillion Market

"Private equity is the biggest bubble in the history of bubbles." —Jared Dillian

AT A GLANCE:

The global private equity market has experienced explosive growth from $579 billion in 2000 to over $8 trillion today.

Much like the growth and financial engineering that fueled the mid-2000s mortgage bubble, we've hit peak levels in the private equity cycle. An unwinding is imminent.

-

The Next Big Short exposes the hidden risks of private equity and private credit that are threatening financial stability.

As the private equity bubble unwinds, investors can now position themselves to protect their wealth and potentially profit from a market shift on par with the Global Financial Crisis.

Editor's Note: Throughout this white paper, "Private Equity" will often be referred to as "PE" and both terms will be used interchangeably, at my discretion.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1... The Explosive Growth of Private Equity

Chapter 2... Deals Vanish and Volume Declines

Chapter 3... Cracks in the "Buzziest" Corner of Wall Street—Private Credit

Chapter 4... Pension Fund Problems

Chapter 5... Sentiment Extremes

Chapter 1: The Explosive Growth of Private Equity

- The Rise of Private Equity

- Longer Hold Times: A Symptom of Distress

- And More

The Rise of Private Equity

Private equity has exploded in popularity since the beginning of the 2010s during periods of low interest rates.

In 1980, there were 24 PE funds.1 By 2015, this number had increased to approximately 6,600. By 2022, there were 17,0002 private equity firms in the United States.

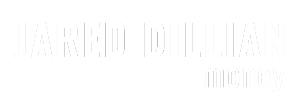

The growth of assets under management (AUM) in private equity has been equally impressive. In 2000, PE firms collectively managed $579 billion. By 2022, this figure surged to about $7.8 trillion.

In North America, the PE industry ballooned to $4 trillion.

Two of the bigger PE firms worth mentioning:

KKR: Started in 2005 managing $15 billion in AUM. Today, it manages $575 billion, a 3,733% increase.3

Blackstone: Started in 1985 with $400,000 and now manages over $1 trillion.

The rapid pace of this astonishing growth is eerily reminiscent of the rise of mortgage-backed securities in the mid-2000s…

Which is exactly why you should care.

Let's take a step back and remember the cause of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008.

Real estate, specifically the mortgage market, was the epicenter.

The shenanigans in the mortgage market and the subsequent collapse of real estate prices led to a global recession.

By 2006, the mortgage industry represented a significant portion of the economy—mortgage debt of US households reached 97% of GDP, and 40% of net private-sector job creation between 2001 and 2005 was in housing-related sectors.

Yet its collapse nearly brought down the entire global financial system.

Millions of people were affected, with devastating losses across the board.

In the United States, the stock market plummeted, wiping out nearly $8 trillion in value between late 2007 and 2009.

Unemployment climbed, peaking at 10% in October 2009.

And between October 2008 and April 2009, an average of 700,000 American workers lost their jobs each month.

The stock market crash wiped out billions in retirement savings, and it took years for the economy to recover.

Many of the biggest banks and insurance companies had to be bailed out, while others collapsed under the weight of their bad investments.

Governments slashed interest rates and flooded their economies with cash in a desperate effort to save the world as we know it.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500 lost more than 50% of their value, and it wasn't until March 2013 that they fully recovered.

Americans lost $9.8 trillion in wealth as their home values plummeted and their retirement accounts vaporized—some investors never fully recovered.

Today, the private equity market is a dominant force in the economy, mirroring that of real estate and mortgages before the GFC.

The private equity industry and private-equity-backed companies directly employ more than 11.7 million workers in the United States… roughly the population of Ohio.

In 2020, private equity was credited for generating $1.4 trillion of gross domestic product (GDP), or about 6.5% of total GDP.

You might think, "I'm not a private equity investor, so why should I care?"

Remember that during the GFC, not many people knew what a mortgage-backed security was, or negative amortization, or the risks of an adjustable-rate mortgage.

But the few investors who saw the collapse coming were able to position themselves to not only protect their wealth but also become fabulously wealthy within a short time.

The same opportunity could be on the horizon with private equity.

So, while the rise of KKR, Blackstone, and others may seem impressive, it's important to realize that history might be repeating itself—this time with private equity at the center.

If you are going to a restaurant, a car wash, or a dentist's office, there is a good chance that it is owned by private equity.

And you have probably noticed that service has deteriorated, and prices have increased.

The reason is that there is a mismatch in priorities between the founder of a business and the private equity owner of a business. The founder of a business thinks long-term : How do I please customers and keep them coming back? A private equity owner only thinks about short-term profitability: How do I extract the most value out of each customer and transaction?

Also, once a private equity owner has extracted all the value possible out of the business, he doesn't care if it goes bankrupt. But a founder cares and will do whatever it takes to stay in business. A founder will keep employees around for morale or other intangible reasons—a private equity owner will fire them remorselessly.

It is this mismatch in priorities between the founders and the PE owners they sell to that creates most of the problems we are experiencing.

Due to this alarming growth, finding new deal flow has become problematic. There simply aren't enough available companies to roll up.

As a result, PE firms have been forced into downgrade markets and are acquiring less-than-ideal businesses that have lower margins and less growth potential compared to more traditional high-return investments.

Examples of downgraded markets include recent acquisitions in digital comics4, smoothie shops5, bakeries6, car washes7, and laundromats.8

Longer Hold Times: A Symptom of Distress

Private equity companies need quick turnaround times to meet investor demand, free up cash, and expand their businesses. Their goal is to buy an underperforming business with stable cash flows, make it more efficient, turn it around, and sell it at a higher valuation.

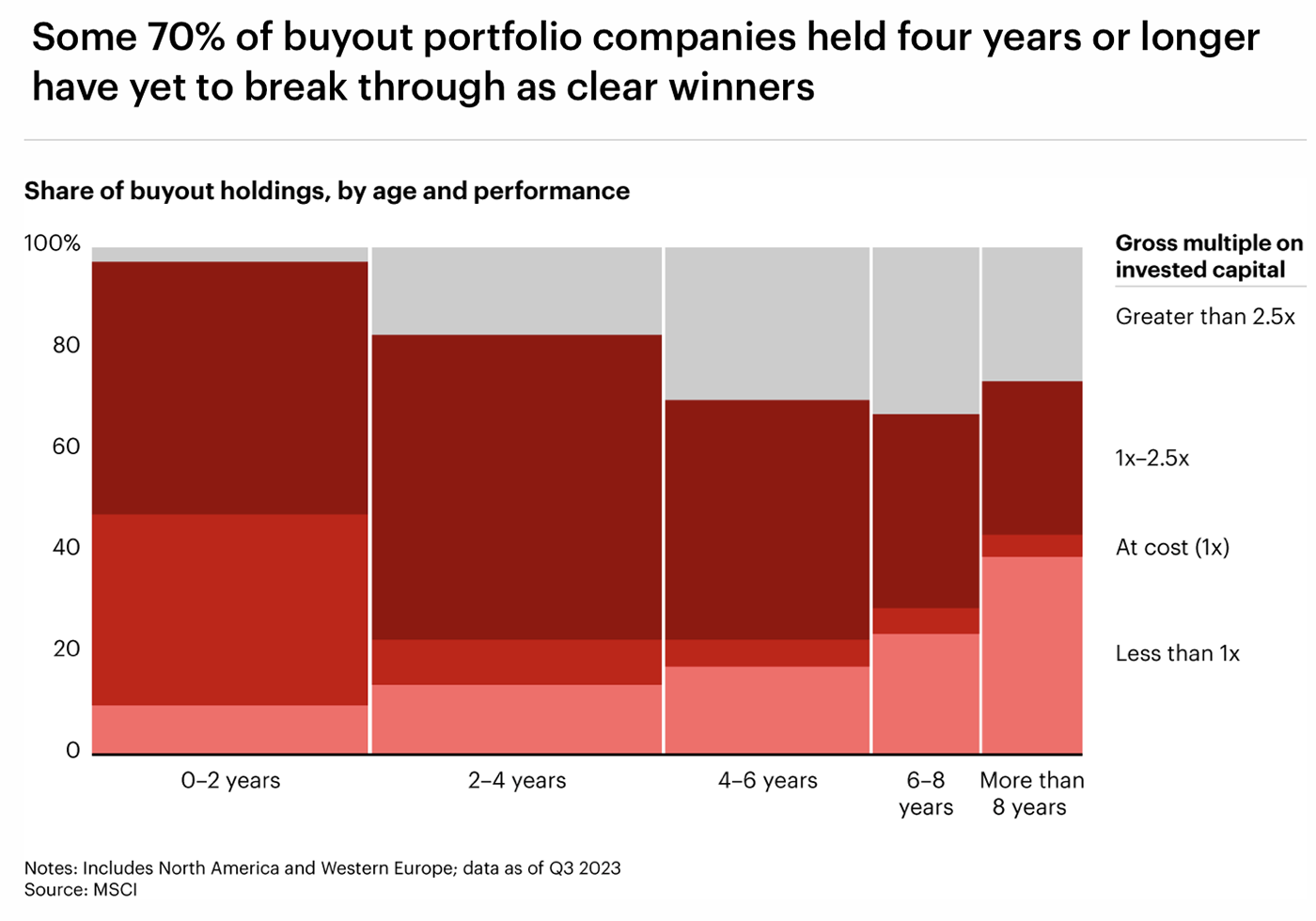

Typically, they hold onto portfolio companies for an average period of three to five years9, although sometimes longer.

But due to economic conditions in recent years, the median holding period has lengthened to nearly six years.10

In 2023, the number of companies held for five years or more increased by 18% year over year.11

Also, companies held for four years or more made up 46% of the total, the highest level since 2012.12

Portfolio companies are being held for a record amount of time as private equity firms are struggling to exit their investments creating a bottleneck in the PE lifecycle. If PE firms can't exit, they can't return cash to their investors (called "limited partners"), then the limited partners get upset and threaten to redeem their shares.

This raises questions about the future stability of the industry and its ability to continue delivering expected returns since private equity portfolio companies are being held for record amounts of time.

The longer companies are held by firms, the lower actual returns go.

For many years, private equity firms delivered double-digit growth with limited volatility, exactly what you are looking for if you are a pension fund or an endowment.

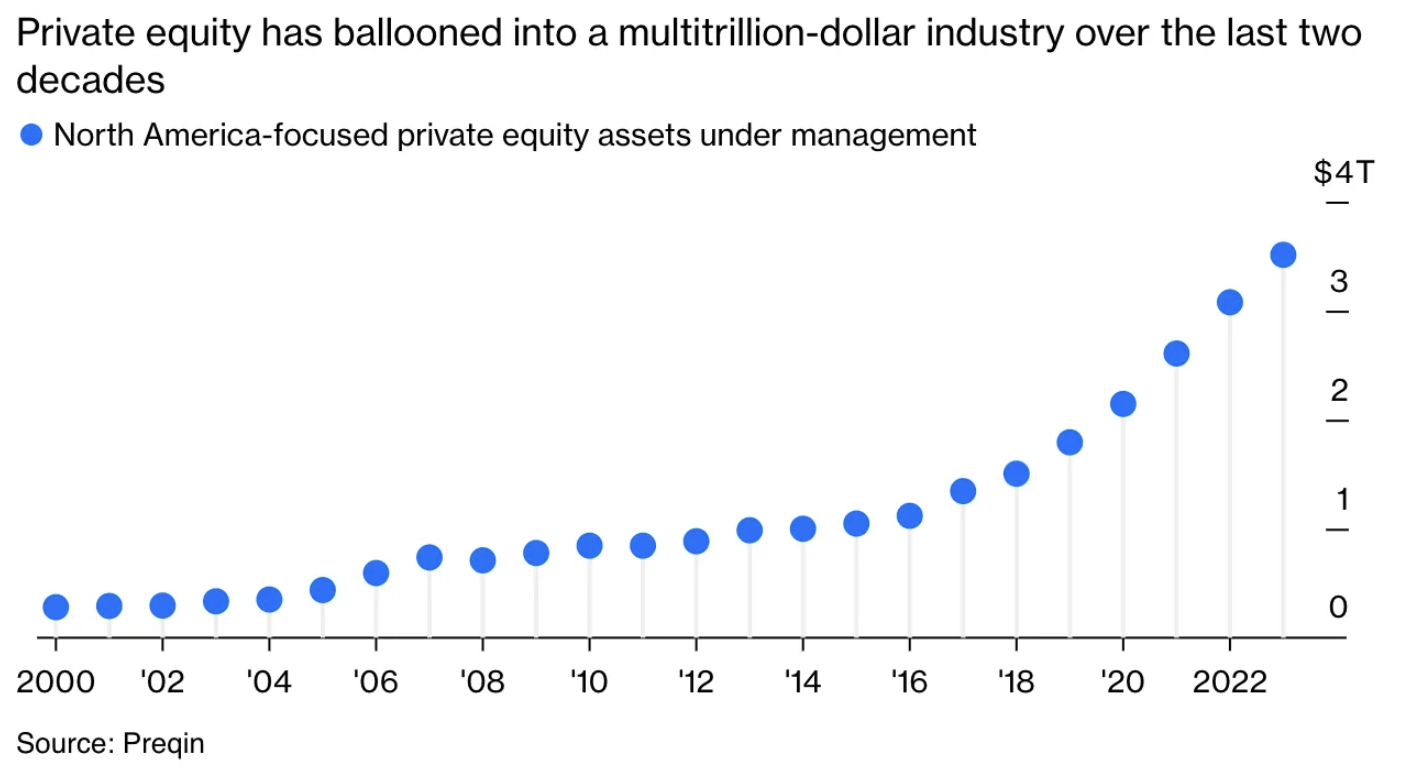

But now, 36% of companies held for six years or longer are now just at breakeven or below… with some barely breaking even.13

Furthermore, a staggering 70% of buyout portfolio companies held for four years or longer have yet to break even.14

The best-case scenario is that returns will be diminished going forward, possibly making it less attractive to endowments.

The worst-case scenario is a recession with no exit in sight, where private valuations drop to match lower public ones, and investors simultaneously demand their money back. This could lead to portfolio companies being sold at massive losses, resulting in the loss of hundreds of thousands, even millions, of jobs nationwide.

If things really start to break, it could trigger a cascade of effects across the financial system.

First, as private equity-owned businesses struggle and potentially default on loans, what would follow would be the credit crunch of the century.

If private credit funds can't meet their commitments, what would follow would be the credit crunch of the century.

There would be interbank lending seizures, a credit markets freeze, and short-term funding would dry up.

At the same time, the jobs of 11.7 million people would be in jeopardy.

For instance, In 2005, the mortgage industry employed around 535,000 people.

But after the crisis in late 2010, this number had plummeted to approximately 246,000… a 54% reduction in the mortgage workforce.

If private equity collapses to levels seen after the financial crisis, a potential 54% reduction in the industry would mean approximately 6.32 million jobs lost, which would be the equivalent of the entire population of Maryland.

The sudden surge in unemployment could send shockwaves through the markets and the economy, leading to reduced consumer spending, lower corporate earnings, and the potential collapse of the stock market.

And considering the US labor force typically consists of about 160–165 million people, that's nearly a 4% hit.

That is the worst-case scenario. Given the 10-year lockup on any given private equity fund, they may be able to earn their way out of it over time, but I am doubtful. Margin calls are rarely orderly.15

Chapter 2: Deals Vanish and Volume Declines

- Regional Decline

- Exit Decline

- The Impact of Record-Dry Powder

- PE Distribution Decline

- Capital for New Fundraising Declines

- And More

The recent (and rapid) rate hike cycle by the Fed in 2022 created a world of uncertainty for private equity. Private equity makes sense when rates are at zero and you can buy companies for 4X or 5X earnings, but when rates are at 5% and you're buying companies for 10X or 12X earnings, it's a problem.

Want to continue reading The Next Big Short: The Private Equity Exposé?

Fill out the form below for full access to this critical research.

Your email is safe with us. We respect your privacy and will never share your information. Read our privacy policy here. Plus, by signing up, you'll also receive Jared's FREE weekly letter, The Jared Dillian Letter, so you can keep up with his latest insights and analysis every week.

READ IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES HERE.

YOUR USE OF THESE MATERIALS IS SUBJECT TO

THE TERMS OF THESE DISCLOSURES.